Their most eloquent writing and preaching grew from a practical desire to communicate truth.

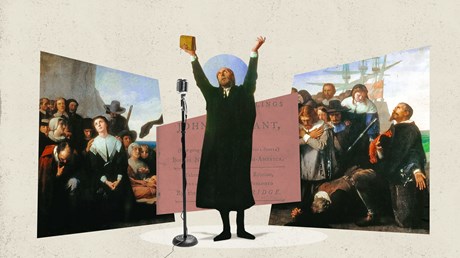

Conversion is central to the Christian faith. From Jesus’ words to Nicodemus in John 3:3 telling him that one must be “born again,” to Saul’s dramatic encounter on the road to Damascus, to the many famous conversion stories that fill the pages of church history, the act of conversion of is essential to Christian life and teaching.

Yet the understanding of what conversion consists of, the representations of that understanding and the means of persuading people toward it—these are far from static. Indeed, conversion came to have such a renewed emphasis within Christian religious experience during the late 17th and early 18th centuries (first in England, then in America and beyond) that this rekindling gave rise to a movement that would come to be called evangelicalism. This “conversionism” was later identified by church historian David Bebbington as one of the evangelical movement’s four characteristic elements, together known as Bebbington’s quadrilateral.

The roots of the evangelical emphasis on conversion are planted in Puritan soil. Despite the Puritans’ undeserved reputation for dry reason and dour imagination, Puritan thinkers and writers produced vivid, compelling prose (and poetry) steeped in both rich imagination and profound reasoning. The Puritans were, in fact, masters of rhetoric. But theirs was not eloquence for the sake of eloquence, something Paul warns about in 1 Corinthians 1:17 (a caution later echoed by Augustine in On Christian Teaching). There is a fine line between eloquence in service of the gospel and that which, in delighting solely in itself, drowns out the message. This is one the themes expertly teased out in The Rhetoric of Conversion in ...

from Christianity Today Magazine

Umn ministry

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)