Governments can’t be indifferent to the moral and spiritual health of the governed.

“Liberalism” is a word with many meanings, some compatible with Christianity, some arguably demanded by it. In its original sense, to be liberal is to exemplify the virtue of liberality, as in broadmindedness or generosity of spirit. More typically, in the United States, liberalism refers to left-wing political views, though “classical” liberalism references a relatively gentle variant of libertarianism.

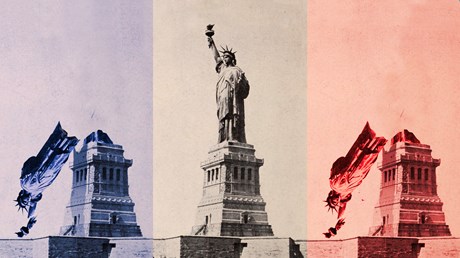

In his new book, Liberalism and its Discontents, however, eminent political scientist Francis Fukuyama sets out to defend liberalism in what may be its deepest sense: the focus on freedom as the highest political good that unites the mainstream American left and right.

Both major political parties, and most American Christians, have embraced this liberal perspective. Republicans tend to seek so-called “negative liberty,” ensuring that the state leaves individuals alone, while Democrats tend to seek “positive liberty,” or state empowerment of the individual. Republicans emphasize economic freedom, while Democrats emphasize sexual freedom. Fukuyama’s treatment reveals, however, why the liberalism at the heart of both approaches is deeply at odds with the Christian political tradition.

Fielding criticisms

Fukuyama opens with a pair of definitions that seem innocuous enough. He calls liberalism a doctrine advocating legal limitations on government and institutional protections for individual rights. In his view, all variants of liberalism 1) favor the individual over the collective, 2) recognize humans as morally equal, 3) emphasize human unity over cultural diversity, and 4) are optimistic about the improvability of the social world.

Chapter 1 lays out three overarching arguments ...

from Christianity Today Magazine

Umn ministry

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)