From the builders of Genesis 11 to the architects of the modern world, we've forgotten who makes our name great.

An excerpt from CT’s Book of the Year. Learn about CT’s 2024 Book Awards here.)

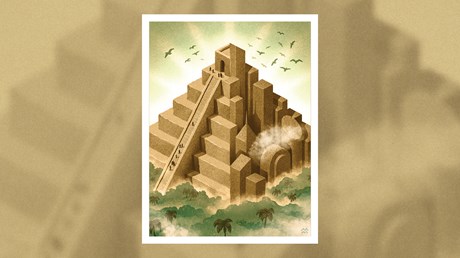

The tale of the Tower of Babel is a story of judgment and a story of autonomy. The events are presented in two acts: the people’s provocation and God’s response.

The curtain lifts for the first act on the scene of a communal building project:

Now the whole world had one language and a common speech. As people moved eastward, they found a plain in Shinar and settled there. They said to each other, “Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly.” They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.” (Gen. 11:1–4)

So what is the problem here? Is it not sensible to live together in cities, with all the benefits of security and the division of labor that urban life brings? Yet there are clues that the main intention is something other than establishing a stable society.

The first humans were commanded by God in Genesis 1:28 to “fill the earth,” but the builders of Babel want to construct a single city, lest they are “scattered over the face of the whole earth.” They want to assert their own autonomous identity, captured in the language of “so that we may make a name for ourselves.” In biblical thinking, to name something is to have authority over it. In Genesis 1, God systematically names the elements of creation as he makes them. To seek to make a name for oneself is to assert one’s independence, ignoring the one who gives you “life and breath ...

from Christianity Today Magazine

Umn ministry

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)