Will fixing inaccurate representation encourage more minorities to “go into all the world”?

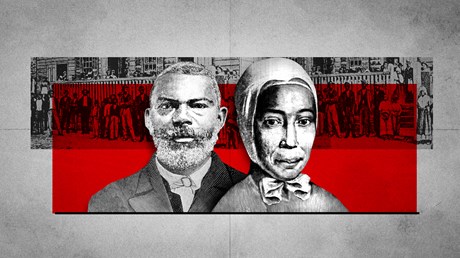

When George Liele set sail for Jamaica in 1782, he didn’t know he was about to become America’s first overseas missionary. And when Rebecca Protten shared the gospel with slaves in the 1730s, she had no idea some scholars would someday call her the mother of modern missions.

These two people of color were too busy surviving—and avoiding jail—to worry about making history. But today they are revising it. Their stories are helping people rethink a missionary color line and, as National African American Missions Council (NAAMC) president Adrian Reeves said at a Missio Nexus conference in 2021, challenging the idea that “missions is for other people and not for us.”

African Americans today account for less than 1 percent of missionaries sent overseas from the US. But they were there at the beginning.

“We have a representation problem,” Reeves said. But “when we share with the Black church their history and legacy in missions, it makes it easier for them to connect.”

That was Noel Erskine’s experience too, when he discovered Liele’s name in the archives of the Great Britain Baptist Missionary Society. The Emory University historian said that growing up in Jamaica, he didn’t really think missionaries could be Black.

“We always associated missionaries with white people,” he said. “They’re a stranger to the culture. We’re not sure of motives.”

British missionary William Carey is often called the father of modern missions. Adoniram Judson has been titled the first American missionary to travel overseas. But both Liele and Protten predated them. Their stories add depth and complication to the sometimes too-simple narrative of ...

from Christianity Today Magazine

Umn ministry

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)